By Grusha Andrews –

I think all of you have heard about Dr Tush Wickramanayaka’s struggle against corporal punishment. Few days ago, the highest court of the land deemed her fundamental rights petition, seeking justice for her daughter subjected to corporal punishment at Gateway International School, not worthy of leave to proceed. If an ex-Prime Minister’s daughter, a “privileged woman” by Sri Lankan norms, cannot negotiate even a crumb of justice from the judiciary for an eleven year old child, we can only imagine the plight of the “commoner” seeking justice.

On March 22, 2019, the Supreme Court has refused granting leave to proceed Dr Tush Wickramanayaka’s fundamental rights case seeking justice for her daughter.

In this backdrop, this is the Part 2 of my previous article on the subject of corporal punishmentand child abuse titled “First Child Abuser Of Sri Lanka”.

Child Abuse – How Big Is The Problem?

On 24th March 1996, Prof Harendra De Silva, renowned paediatrician delivered a keynote address at the Annual Sessions of the Sri Lanka Medical Association (SLMA) where Dr. Tara de Mel was the Secretary to SLMA and was also an advisor to President Chandrika Kumaratunga.

Since the early 90s Prof Harendra De Silva has been an advocate for child rights in general. Upon the request of a group of media personnel he initiated a series of public lectures and media interviews on the subject. Independent of De Silva, certain NGOs such as Don Bosco and PEACE had lobbied President Kumaratunga against sexual exploitation of children by tourists and issues on child soldiers.

Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga – Pioneer Of Reform

It was almost always the natural tendency of President Kumaratunga to spend most of her office in self-destructive political practice which earned her the disdain among her colleagues and people, rapidly declining her initially unprecedented popularity to the pits of the political earth. However, the child rights activists would forever remember her as the one politician who had the vision to initiate the ground breaking policy reforms in the sphere of child rights.

*In 1994, as the Chief Minister of the Western Province, Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga, took up the issue of sexual exploitation of children by foreigners. Later as President she spearheaded law reforms that resulted in the Penal Code (amendment) Act No. 22 of 1995. The highlight of the amendment was a provision that strengthened the law governing sexual offences and offences against children. The amendment concentrated on defining offences that were previously not defined or described adequately. Further they increased sentences, and included mandatory jail sentences for some offences.

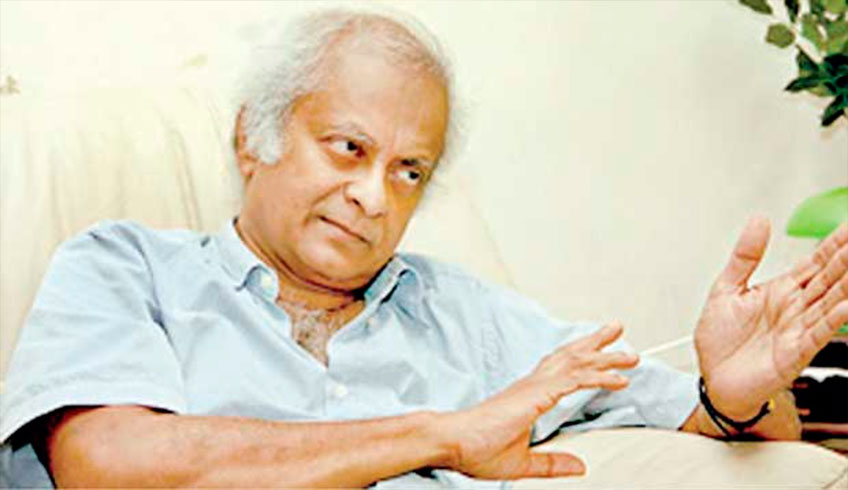

Professor Harendra De Silva – Unsung Hero

In December 1996, President Kumaratunga appointed a task force on child protection, chaired by Prof Harendra De Silva. De Silva’s commitment and expert contribution was largely considered a tipping point of the Child Rights discourse in Sri Lanka.

* The task force recommended several legal amendments, including the establishment of a National Child Protection Authority (NCPA). In addition, the task force recommended a number of amendments to existing law that were subsequently enacted and are now in force. These are:

* The new amendment to the judicature act dispensed with the non-summary inquiry in the case of statutory rape (the rape of children below sixteen years of age). This reduced the duration of the court procedure that the child must undergo. Previously practiced preliminary hearing was often protracted and sometimes psychologically traumatised the child.

* Expansion of the magistrate’s authority to detain alleged perpetrators of child abuse (Code of Criminal Procedure Amendment, Act No. 28 of 1998). Previously, the magistrate was only empowered to detain an alleged perpetrator of child abuse for investigative purposes without a warrant for one day. The new amendment expanded this period of investigative detention to three days. It also gave priority to cases of child abuse and introduced a referral form for victims of child abuse.

* Increasing the scope of prohibited conduct. For example, Act No. 29 of 1998 amended the penal code to prohibit the use of children for purposes of begging, procuring sexual intercourse, and trafficking in restricted articles. The amended penal code also imposes a legal obligation on developers of films and photographs to inform the police of indecent or obscene material involving children.

* The presidential task force recommended other legal amendments that are now in the process of being enacted and implemented. One proposed amendment was the Evidence Ordinance that would admit video evidence of’ a child witness’s preliminary interview. Other recommendations were, dispensing with the requirement that a child witness take an oath and enabling age indication on a doctor’s certificate to serve as prima facie proof of age where age is relevant in a case and there is no better evidence available.

Birth Of The National Child Protection Authority (NCPA)

* One of the most important recommendations of the presidential task force on child protection was the establishment of a National Child Protection Authority (NCPA). The NCPA bill was presented in Parliament by the Minister of Justice in August 1998 and was passed unanimously in November 1998 (NCPA Act’, 1998). The act was gazetted in January 1999, and the board of the NCPA was appointed in June 1999. Prof Harendra de Silva was its first chairman.

Scope Of the NCPA

The NCPA’s mandate included a broad range of authority, objectives, and duties. They included the following:

Advising government on national policy and measures regarding the protection of children and the prevention and treatment of child abuse

Consulting and coordinating with relevant ministries, local authorities, and public and private sector organisations and recommending measures for the prevention of child abuse and the protection of victims

Recommending legal, administrative, and other reforms for the effective implementation of national policy

Monitoring the implementation of the law and the progress of investigations and criminal proceedings in child abuse cases

Recommending measures regarding the protection, rehabilitation, and reintegration into society of children affected by armed conflict

Taking appropriate steps for the safety and protection of children in conflict with the law (i.e., “juvenile offenders”)

Receiving reports of child abuse from the public

Advising and assisting local bodies and NGOs to coordinate campaigns against child abuse

Coordinating, promoting, and conducting research on child abuse

Coordinating and assisting the tourist industry to prevent child abuse

Preparing and maintaining a national database on child abuse

Monitoring organisations that provide care for children and serving as liaison to and exchanging information with foreign governments and international organisations

Many Good Women And Men

To oversee such a broad mandate, the NCPA needed the participation of professionals with a broad range of experience and skills. Hence the NCPA is comprised of:

Paediatricians

Forensic pathologists

Psychiatrists

Psychologists

A senior police officer

A senior lawyer from the Attorney General’s department

Five other members associated with child protection efforts, including members from NGOs

Ex-officio members include the Commissioners of Labor and Probation and Child Care Services, and the chairman of the monitoring committee of the CRC (Convention on the Rights of the Child)

Another panel of ex-officio members would include senior officers from the ministries of Justice, Education, Defence, Health, Social Services, Provincial Councils, Women’s Affairs, Labor, Tourism, and Media.

* The NCPA has the advantage of reporting directly to the President, and the presence of high-ranking officials facilitates the implementation and coordination of mechanisms of’ action suggested at the NCPA meetings.

Corporal Punishment: Is it Really Necessary?

An Education Ministry circular was issued by Dr. Tara de Mel who was the secretary of Education to stop Corporal Punishment. However, it was not made a law through a cabinet paper at the time. Nearly a decade later the Corporal Punishment (repeal) ACT, No. 23 of 2005 was passed banning all forms of corporal punishment on children including whipping.

A small reminder to President Sirisena who wanted to beat up the young bra throwers at the Enrique show with the “madu walige”. No Sir, you can’t. You were elected to uphold the constitution that bans you from doing exactly that!

Judiciary’s Resistance To Eliminating Corporal Punishment

Going back to the mother story of this article, the incident that provoked Dr Tush Wickramanayaka’s fight against corporal punishment began with her (then) 10 year old daughter’s ear being twisted by a teacher who is a habitual imparter of corporal punishment at Gateway International School. The twisting of the ear was followed by making the “offending” children kneel on the floor as punishment. The cultural interpretation and the gravity we may individually assign to such corporal punishment may differ from person to person. This may be true for the respected judges who had no qualms in denying the case the leave to proceed.

Why is the judiciary which should be the biggest soldier upholding our constitution that ensures the rights of the child and stand against corporal punishment give such a verdict? Was it because the judges are not the super human demigods with clarity of mind that we hope they are when we pray our cases, sorrows and losses before them?

Is it because they too were abused as children and now want to reconcile their abused childhood by trivialising the violation of the constitution through implementing corporal punishment long after it has been outlawed?

Is it because they themselves have beaten up their children at home and are reconciling their own past of aggression?

Is it because they are just human?

Is it because the bench were all men?

Is the Boys Club of the triad of law – politics – media this powerful to override our constitution?

Was it a technicality that the revered judges had to adhere to, leading the denial of leave to proceed?

Why, why?

It was reported that one of the judges stated that the corporal punishment imparted on this innocent child was a “sulu danduwama” (minor punishment). Who decides what minor corporal punishment is? Who defined it? Where in the law is that written?

More on this later when the official court ruling is available.

Till then, let’s suppress our sighs for the wealth of our nation, our children, who have been given the dangerous message by the highest court in the land that it is ok to beat them up.

* Sections of this article indicated by an asterisk (*) are direct extracts, slightly modified for ease of reading from the book titled “Child Abuse A Global View – Sri Lanka by D.G. Harendra de Silva.

References

Child Abuse – How big is the problem? by Prof. Harendra de Silva. Keynote lecture. Sri Lanka Medical Association Annual Sessions. March 24th 1996. Colombo.

Corporal Punishment: Is it Really Necessary? D.G.H. de Silva, P. Zoysa, N. Kannangara. Published by the National Child Protection authority. 2001. In Sinhala, Tamil and English.

Child Abuse A Global View – Sri Lanka, D.G. Harendra de Silva. – Eds. Swhartz-Kenny, Mc Caulley & Epstein. Greenwood Press, Westport, USA. ISBN 0-313-30745-8